Are There "Real" Alignments?

Some gamers hate the D&D alignment system, saying that it is unrealistic and does not match real-world motivations. Many say that attempting to use the system results in unplayable characters. At any rate, there's no doubt in anyone's mind that the alignment system has sparked decades of debate and discussions on whether to get rid of it outright or to make it more usable.

This page will focus on certain theories in cross-cultural psychology that could relate to the nine-point alignment system of D&D. "Real" alignments will be discussed with the purpose of making each of the nine a "realistic" philosophy.

Overview

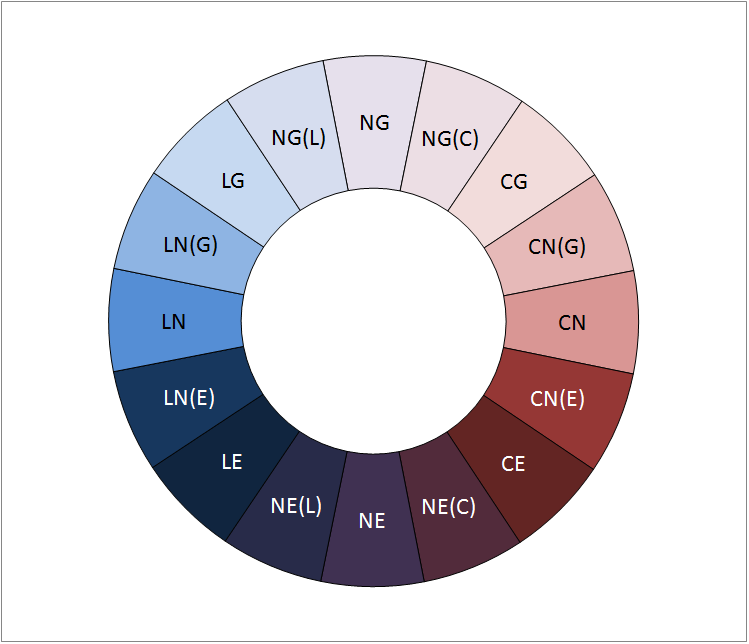

Consider the typical graphic of alignment as a wheel. It is the chief alternate to the "3 X 3" grid view and is the model for the Outer Planes. This ring shows eight of the canonical alignments with all "half-step" alignments between them. True Neutrality resides in the middle (not shown).

If you weren't sleeping in Outer Planar Cosmology 101, you'll remember that the good planes stretch from Arcadia to Gladsheim, while the evil planes swing from Acheron to Pandemonium. The lawful planes go from The Twin Paradises to Gehenna and the chaotic planes from The Happy Hunting Grounds to Tarterus. These planes form a circular continuum of alignment tendencies ranging from lawful through good through chaotic through evil and back to lawful. Alignments which are not mutually exclusive can be combined and neutrality represents the middle ground between dichotomies.

The "divisions" between these alignments are drawn with solid lines, but no such lines exist in reality. One alignment shades into the next and whole ring is simply a circular continuum. With this model, all alignments shade into neutrality the closer one moves to the center.

Alignment Names

The names of the alignments themselves seem to indicate that the alignments are viewed from the lawful good point of view. Being called "lawful" seems to be better than being called "chaotic" while "good" is vastly better than the pejorative term "evil." But do chaotics really see themselves as unpredictable, impulsive and perhaps a little bit dangerous? Or do they see themselves as independent, free-thinking, and unfettered by the unnecessary restrictions of society? Likewise, evil characters are more likely to see themselves as determined, self-reliant, and steadfast in their beliefs rather than seeing themselves as ruthless, cruel, or selfish. In essence, no character ever believes that their particular world-view and values system is inferior or wrong, otherwise why would they adhere to it?

This being said, it might be important to take a look at the proposed qualities that members of each alignment believe themselves to possess. For this, the normal "3 X 3" alignment grid is shown with two adjectives giving a simple self-description for each alignment. This isn't meant to completely sum up each alignment's assessment of itself. This is simply a snapshot as to how each alignment might characterize its two components.

| Lawful Good Honorable and Humane |

Neutral Good Practical and Humane |

Chaotic Good Independent and Humane |

| Lawful Neutral Honorable and Realistic |

True Neutral Practical and Realistic |

Chaotic Neutral Independent and Realistic |

| Lawful Evil Honorable and Determined |

Neutral Evil Practical and Determined |

Chaotic Evil Independent and Determined |

With this we note that lawful good sees itself as honorable and humane. Its diametric opposite, chaotic evil, views itself as independent and determined. Independence and determination are certainly desirable qualities. Chaotic good is independent and humane. Once again, these two qualities can be seen as desirable. Lawful evil sees itself as honorable and determined. This is a very desirable combination when someone needs to be trusted and use every means to get the job done, right?

(And this isn't to say that good characters can't be determined and that lawful characters can't act independently. Even evil characters can act with humanity when necessary, while chaotics can act honorably on occasion.)

Alignments: The Positives and the Negatives

The point of this exercise is to show that even though there are "chaotic" and "evil" alignments in D&D, members of these alignments can still possess character traits that are deemed desirable, perhaps even heroic. It naturally follows, then, that each alignment can be seen in terms of "positive" and "negative" attributes. We already know the negative attributes of the evil alignments; the D&D alignment system focuses on them exclusively. Evil characters are extremely selfish, cruel, merciless, and are typically unconcerned with the welfare of those considered not part of the "in-group." In the case of lawful evils, the in-group is clearly defined. For neutral evils, the in-group is whoever is contributing to advancing the aims of the neutral evil. For chaotic evils, the in-group is simply the self.

In a similar vein, D&D focuses only on the positive aspects of the good alignments. Good characters are benevolent, altruistic, and self-sacrificing. They "do the right thing." They help people, fight evil, and aid good organizations. These are all positive aspects of goodness. What are the negative aspects? Good characters can be pacifists, refusing to ever use violence, even if such violence combats evil and saves lives. Good characters can be martyrs, sacrificing the self to such an extent that they become doormats for anyone who comes along (good or evil). They can be self-righteous. Certainly a "holier than thou" attitude is a negative one. There are many other examples of good characters possessing negative traits based on their goodness.

The same sort of "positive chaotic" versus "negative lawful" comparison can be shown as well.

How should this concept of the positive, negative, and neutral be used with respect to the alignment system? Should a third axis be created such that we have positive chaotic evils and negative chaotic goods in a Rubik's Cube-like model of the alignment system? This needlessly complicates an already complicated system, so this will not be explored. However, I postulate that D&D normally takes a diagonal cross-slice out of this alignment cube and gives us the following system:

| Lawful Good (Positive) |

Neutral Good (Positive) |

Chaotic Good (Positive) |

| Lawful Neutral (Neutral) |

True Neutral (Neutral) |

Chaotic Neutral (Neutral) |

| Lawful Evil (Negative) |

Neutral Evil (Negative) |

Chaotic Evil (Negative) |

Instead of this, I propose to take a slice off of the top of the alignment cube, a slice that will give us heroes regardless of whether the previous alignment was labeled "lawful good" or "chaotic evil." I propose a system of "positive" alignments that have all nine of the canonical alignments, but allow for playable characters regardless. Villains are relegated to the bottom, "negative" slice of this theoretical alignment cube (whether lawful good or chaotic evil).

Universals in the Content and Structure of Values

So, how can such a "positive" alignment system be contructed? How can we have a "positive" chaotic evil character? The very concept seems to defy logic and boggles the mind.

To lay the foundation for this construct, we turn to concepts developed by Shalom Schwartz concerning universals in value systems. (1) Schwartz theorizes that there are ten motivations that act as guides for action in life. These motivations are universal, meaning that they've been empirically determined to exist across all of the world's cultures. These ten motivations are: self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence, and universalism. Each of the ten basic values can be characterized by describing its central motivational goal and its associated single values. (2)

Self-Direction - Independent thought and action; choosing, creating, exploring. Associated single values are: freedom, creativity, independence, choosing one's own goals, being curious, having self-respect.

Stimulation - Excitement, novelty, and challenge in life. Associate single values are: having an exciting and varied life, being daring.

Hedonism - Pleasure and sensuous gratification for oneself. Associated single values are: experiencing pleasure and enjoying life.

Achievement - Personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards. Associated single values are: being ambitious, influential, capable, successful, intelligence, and having self-respect.

Power - Social status and prestige, control or dominance over people and resources. Associate single values are: having social power, wealth, and authority, preserving one's own public image, and having social recognition.

Security - Safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and of self. Associate single values are: ensuring national security, reciprocation of favors, ensuring family security, having a sense of belonging, preserving the social order, being healthy and clean.

Conformity - Restraint of actions, inclinations, and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms. Associated single values are: being obedient, having self-discipline, being polite, honoring parents and elders.

Tradition - Respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide the self. Associated single values are: respecting tradition, being devout, accepting one's own portion in life, being humble, and taking life in moderation.

Benevolence - Preserving and enhancing the welfare of those with whom one is in frequent personal contact (the "in-group"). Associated single values are: being helpful, responsible, forgiving, honest loyal, and having mature love for others and true friendships.

Universalism - Understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection for the welfare of all people and for nature. Associated single values are: advancing equality, being one with nature, having wisdom, filling the world with beauty, advancing social justice, being broad-minded, protecting the environment, and see the world at peace.

These ten motivations also show patterns of compatibility and conflict. The following compatibilities have been noted.

Power and Achievement - both emphasize social superiority and esteem.

Achievement and Hedonism - both are concerned with self-indulgence and self-centeredness.

Hedonism and Stimulation - both entail a desire for affectively pleasant arousal.

Stimulation and Self-Direction - both involve intrinsic motivation for mastery and openness for change.

Self-Direction and Universalism - both express reliance on one's own judgment and comfort with the diversity of existence.

Universalism and Benevolence - both are concerned with enhancement of others and transcendence of selfish interests.

Benevolence and Tradition/Conformity - both promote devotion to one's in-group.

Tradition and Conformity - both stress self-restraint and submission. These two are combined by Schwartz in later versions of the theory.

Tradition/Conformity and Security - both emphasize conservation of order and harmony in relations.

Security and Power - both stress avoiding or overcoming the threat of uncertainties by controlling relationships and resources.

The following conflicts occur.Self-Direction and Stimulation versus Conformity, Tradition, and Security - This dimension reflects a conflict between emphases on own independent thought and action and favoring change versus submissive self-restriction, preservation of traditional practices, and protection of stability.

Universalism and Benevolence versus Achievement and Power - This dimension reflects a conflict between acceptance of others as equals and concern for their welfare versus pursuit of one's own relative success and dominance over others.

Given these compatibilities and conflicts, these ten primary motivations seem to suggest a circular continuum of values. A graphic representing this is shown below.

It's not hard to take a conceptual leap and begin to identify certain values as being the primary motivators for certain alignments. Indeed, in later studies, four super-groupings are postulated. Power and Achievement belong to the Self-Enhancement group while Benevolence and Universalism are said to be in the Self-Transcendence group. Conformity/Tradition and Security are in the Conservation group. Finally, Self-Direction and Stimulation are said to be in the Openness to Change group. The Hedonism motivation is split between the Self-Enhancement and Openness to Change groups.

Christian Welzel of the World Values Survey identifies the Self-Transcendence group with altruism, the Self-Enhancement group with egoism, the Conservation group with collectivism, and the Openness to Change group with individualism. (3)

It seems clear that the D&D alignment chart can be placed over this "real-world" analysis of the various value systems like so:

The various alignments have as their primary motivations the following values:

Lawful Good - Conformity/Tradition and Benevolence

Neutral Good - Benevolence and Universalism

Chaotic Good - Universalism and Self-Direction

Chaotic Neutral - Self-Direction and Stimulation

Chaotic Evil - Hedonism

Neutral Evil - Achievement and Power

Lawful Evil - Power and Security

Lawful Neutral - Security and Conformity/Tradition

True Neutral - Any values, whether incongruent or not, can serve as motivations for True Neutrals. True Neutrality can indicate no strong preference for a set of motivations (i.e., most motivations are of equal strength) or a tendency to be motivated by values that are normally incongruent (such as Benevolence and Power or Security and Self-Direction).

Half-Step Alignments - The value shared by the two alignments it falls between.

It should be noted that although the primary motivations are likely to be those listed above, they are not necessarily the only motivations. The motivations for a character become less likely the further they are from the character's alignment. For example, a lawful good character could be motivated by Universalism or Security (as well as Tradition/Conformity and Benevolence) but these motivations are less likely. It is very unlikely that this character would be motivated by Power or Self-Direction and extremely unlikely that they would be motivated by Achievement, Hedonism, or Stimulation.

And it must be said that although this overlay shows that the "evil" alignments are motivated by Security, Power, Achievement, and Hedonism, in real life, these motivations do not necessarily produce "evil" individuals in the D&D sense. In fact, many people are certainly motivated to provide for their own Security and increase their own Power within society; these pursuits do not make them lawful evil (like a D&D villain). This is why it is important to change the terminology for naming the alignments if all alignments are to become playable.

So, our "positive" chaotic evil is simply a pure hedonist. This sort of character is concerned with themselves and their own pleasure. They avoid pain, hardship, and discomfort through any means available. They seek wealth because pleasure can be purchased. They want others to work for them, so as to avoid the pain of labor. They will lie in seeking pleasure and also if telling the truth would bring them discomfort.

New Names for Old Alignments

As stated previously, the old alignment names just won't do anymore. A pleasure-loving thrill-seeker cannot be called "chaotic evil." There's just too much baggage associated with that description and it really doesn't apply. I suggest the following one-word names for the new "positive" alignments.

Righteous (Lawful Good) - Conformity/Tradition and Benevolence

Humane (Neutral Good) - Benevolence and Universalism

Transcendent (Chaotic Good) - Universalism and Self-Direction

Autonomous (Chaotic Neutral) - Self-Direction and Stimulation

Sybaritic (Chaotic Evil) - Hedonism

Ambitious (Neutral Evil) - Achievement and Power

Ascendent (Lawful Evil) - Power and Security

Orthodox (Lawful Neutral) - Security and Conformity/Tradition

Pragmatic (True Neutral) - (any values)

These names, of course, are arbitrary. Gaming groups could decide to adopt similar terms that suit their particular view of the alignment system. The purpose is to remove the traditional alignment names so that characters of all alignments can be played. These new alignments could also be seen as paths followed by characters. In this case, suggested path names are listed.

Path of Integrity (Lawful Good) - Conformity/Tradition and Benevolence

Path of Mercy (Neutral Good) - Benevolence and Universalism

Path of Liberty (Chaotic Good) - Universalism and Self-Direction

Path of Autonomy (Chaotic Neutral) - Self-Direction and Stimulation

Path of Luxury (Chaotic Evil) - Hedonism

Path of Supremacy (Neutral Evil) - Achievement and Power

Path of Ascendency (Lawful Evil) - Power and Security

Path of Harmony (Lawful Neutral) - Security and Conformity/Tradition

Path of Equity (True Neutral) - (any values)

Conclusion

Are there "real" alignments? If by alignment, we mean the motivations and values of an individual that serve as guiding principles in life, then yes, there are real alignments. Furthermore, when certain universal motivations serve as the primary values of an individual, it seems that some motivations are compatible while other motivations are less likely to be included in that individual's value system. This brings about a circular continuum of values, much like the "ring" alignment model. Although these universal motivations are different from the traditional alignments, there are parallels that can be drawn between the two systems. Knowledge of these parallels can be used to create a more "realistic" alignment system and finally make the alignment system a tool for creating interesting characters rather than uninteresting caricatures.

(1) Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25) (pp. 1-65). New York: Academic Press.

(2) Schwartz, S.H. (1996). Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. In C. Seligman, J.M. Olson, & M.P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario Symposium, Vol. 8 (pp. 1-24). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

(3) Welzel, Christian (2010). How Selfish are Self-Expression Values? A Civicness Test. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 41, Issue 2 (pp. 152-174).